“The Girl on the Train” Misses Its Destination

Written by: Christopher Llewellyn Reed | October 7th, 2016

“The Girl on the Train” Misses Its Destination

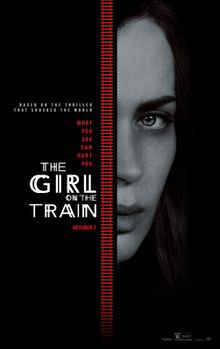

The Girl on the Train (Tate Taylor, 2016) 1½ out of 4 stars

To how many metaphorical uses can we put trains? Their gleaming hulls first arrived in the early 19th century, revolutionized mass transportation, and quickly became symbols of modernity and the human condition. Among other ideas, they represent, in art, the journey through life, filled with structured itineraries and random meetings. Think the daily commute in Patricia Highsmith’s 1950 debut novel Strangers on a Train, which Alfred Hitchcock promptly turned into a deeply unsettling eponymous film about a chance railway encounter that quickly turns psychotic: you never know who you might meet on your daily commute! Or consider the train under which poor Anna Karenina throws herself in the novel that bears her name; Soviet director Mikhail Kalatozov borrowed that scene for a terrifying moment in his 1957 WWII drama The Cranes Are Flying. There can even be a decidedly sexual innuendo to the manner in which trains forge ahead, plunging into tunnels as they go; Hitchcock, again, used just that image to end his 1959 espionage thriller North by Northwest. And on and on.

Now, not quite two years after its publication (about as fast a turnaround as Highsmith enjoyed), author Paula Hawkins’ bestselling, if convoluted, 2015 drama-thriller (let’s call it a “driller”) The Girl on the Train comes to the big screen, courtesy of Tate Taylor (The Help). Not to be confused with a fine French film, from 2009, of the same title (in English), it possesses the same weaknesses as its source, for better or for worse. I was certainly no great fan of Hawkins’ work, yet I tried to approach the movie with an open mind. After all, the central visual metaphor of an alienated person viewing snippets of others’ lives from the windows of a passing train is a perfect representation (minus, perhaps, the alienation) of the act of viewing films. Add a dash of unseemly voyeurism, and it’s Hitchcock all over again. Nothing wrong with that. And yet, it’s largely an overwrought mess, albeit one with a fine central performance from Emily Blunt (Edge of Tomorrow) as the titular “girl.”

Blunt plays Rachel, a thirtysomething woman who spends her days going back and forth to the big city from her suburban home, staring out the window at the houses that flash by, conjuring backstories for the people she sees on a recurring basis. The book is set in London and its environs; the movie transplants it to New York and the counties above (the story neither gains nor loses by this change). We quickly learn that Rachel is an alcoholic, though her cinematic version looks, in spite of Blunt’s minimal makeup (Hollywood’s variant of haggard), less dissipated than Hawkins’ description. Rachel also has an unhealthy obsession with her ex-husband Tom, his new wife, Anna, and their infant child, as well as with another couple, Megan and Scott, Tom and Anna’s neighbors, all of whom Rachel glimpses on her daily commute, and all of which we learn through Rachel’s voiceover narration. She is not to be our only guide, however, as one unreliable narrator is not enough here, and soon we enter into the points of view of both the aforementioned Anna and Megan, as well, shifting not just between perspectives, but also time, jumping from the present to the not-so-distant past, the latter slowly informing the events of the former. And then, one night, Megan goes missing, and what had been seemingly disparate threads of a frayed narrative come together – or try to – as Rachel, her own memory blacked out from booze, tries to piece together the fragments of the mystery.

It’s not without a certain maudlin appeal, and Blunt is very good as a lost woman desperate to reclaim her dignity of self, but the actual thriller elements work no better on screen than they did on the page. Characters, including a detective played by Allison Janney (The Way Way Back), behave in improbable ways, motivated more by narrative needs than actual human psychology. What could have been a truly interesting meditation on the ways that men manipulate women into self-loathing and self-destructive behavior is lost in the melodrama. Both Rebecca Ferguson (so good in Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation) and Haley Bennett (so good in The Magnificent Seven) are largely wasted as the two-dimensional Anna and Megan. Justin Theroux (The Leftovers) and Luke Evans (High-Rise) fare no better as Tom and Scott, nor, especially does Edgar Ramirez (Hands of Stone), as a sexy, if possibly ethically challenged, psychologist. In short, good actors are hampered by an impossible script, and the only one given enough material to rise above the torrid muddle is Blunt, herself. This being a “driller,” there is, of course, a twist at the end, and it is emblematic of this movie’s on-the-nose construction that said twist is delivered via an actual corkscrew (the train, ultimately, is a mere passenger in its own tale). If you like your stories obvious, where everything is spelled out for you, then The Girl on the Train might just work. If not … well, you have been warned.