Christopher Llewellyn Reed’s Take on First Two Weeks of NYFF58

Written by: Christopher Llewellyn Reed | September 29th, 2020

The 2020 New York Film Festival (NYFF) is in its 58th iteration, and runs until October 11 (it started on September 17). Normally, I would not be able to attend, given that I do not live in New York City and the duration makes it difficult for me to figure out the best time to visit, as I might do for shorter festivals. However, because the 2020 version is both virtual and in drive-in theaters, the former aspect makes it easier for a critic like me to access the films, and so this time I applied for accreditation and have been very much enjoying the movies, for the most part. With 25 features from over 19 countries in its Main Slate, an additional 6 films in its Spotlight section, and 14 more in its Currents program (which also includes 8 series of shorts), plus 11 in its Revival collection, this year’s fest offers a robust array of cinematic delights for all who care to sample the wares. What follows is my take on the 10 films (9 features and 1 short) I have seen, so far, starting with my Top 5 of the past two weeks.

TOP 5 of WEEKS 1 and 2 (in Alphabetical Order):

The Calming (Song Fang, 2020) [the paragraph, below, is the first from a longer review I wrote for Hammer to Nail]

Lin Tong is a documentary director in the midst of a mild existential funk following the end of a long-term romantic relationship. When we first meet her, she is in Tokyo, Japan, having traveled there from her native Beijing, China, to present a film of hers in a gallery exhibit. While in the country, she spends time with a former mentor, travels north to Jōetsu for some wintery sightseeing, gorgeous snow and mountains surrounding her as she goes, then heads back home to move into a new place, alone. Before long, she is off again, this time to Hong Kong, after first paying visit to her aging parents, one of whom, her father, is ill. While in Hong Kong, she sees some friends, screens another (or the same) movie, this time in a lecture hall, and then returns to Beijing once more. By then, her father has improved, and even swims laps as she and her mother watch. All the while, wherever she may be, Lin spends long moments on her own, walking through the landscapes of nature and city, and where they intersect, carefully pondering what life next has to offer. Such is The Calming, the sophomore feature from director Song Fang (Memories Look at Me), a lovely, meditative ramble through mundane occurrences that, by the end, add up to something quite profound.

Isabella (Matías Piñeiro, 2020) [the paragraph, below, is the first from a longer review I wrote for Hammer to Nail, which has yet to post as of this writing]

Continuing the technique of embedding Shakespeare into modern life that we last saw in his Hermia & Helena (where A Midsummer Night’s Dream was the text), Argentinian director Matías Piñeiro, in Isabella(the title coming from the main female character in Measure for Measure), crafts a poignant drama about art, inspiration and sisterly love, haunted by evocative visuals and editing. Time folds in on itself, throughout, made more resonant through frequent repetition of similar images and moments. What’s past is prologue, and simultaneously past. Isabella may be a theatrical construct, but she is also eternal.

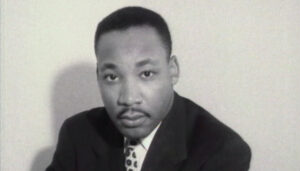

MLK/FBI (Sam Pollard, 2020) [the paragraph, below, is the first from a longer review I wrote for Hammer to Nail]

Documentary director Sam Pollard is no stranger to archival footage, with works like Two Trains Runnin’and Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me (to name but a few) under his cinematic belt, not to mention the many movies he has edited for others, including 4 Little Girls and Chisholm ’72. One might claim he is something of an expert in the genre of historical nonfiction filmmaking, in fact, and with his latest project, MLK/FBI, he puts that skill to marvelous use, delivering an insightful portrait of the life of one of the 20thcentury’s most important figures at a time when he was hounded and harassed by the top law-enforcement agency of the United States. We may think of Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK) today as a beloved Civil Rights icon, but he was not always so cherished while alive, thanks in no small part to the machinations of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). In 104 gripping minutes, Pollard examines the how and the why of the anti-MLK actions undertaken by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, a story that proves extraordinarily relevant to our current moment, given the pushback against nonviolent protests by the current occupant of the White House, aided and abetted by Attorney General Bill Barr. Ignore the lessons of the past at your own present peril.

Night of the Kings (Philippe Lacôte, 2020) [the paragraph, below, is the first from a longer review I wrote for Hammer to Nail, which has yet to post as of this writing]

In his latest film, Ivorian director Philippe Lacôte (Run) explores the intersection of myth, folklore and post-colonial discontent in a gripping jailhouse drama filled with fascinating, three-dimensional characters, each with his own survivalist agenda. Set in Côte d’Ivoire’s capital city of Abidjan’s MACA prison, the movie follows the high-stakes narrative of a new convict thrown into the middle of a deadly power struggle between rival factions. As the mortally ill boss-among-inmates struggles to ensure a smooth handover of authority to his chosen successor, everything is on the existential table. To come out alive, our young hero must tell a tale as fascinating as it is endless, for when the sun rises on the morning of his second day inside, tradition dictates that he be executed once his story is done. Such is Night of the Kings, where fate has no mercy and luck is of your own making.

Nomadland (Chloé Zhao, 2020) [the paragraph, below, is the first from a longer review I wrote for this site]

Nomadland (Chloé Zhao, 2020) [the paragraph, below, is the first from a longer review I wrote for this site]

With her two previous features, The Rider and Songs My Brother Taught Me, Chinese director Chloé Zhao demonstrated not only a strong affinity for the American West, but also a deep understanding of its harsh realities. Now, with Nomadland, a fictional narrative based on the eponymous 2017 nonfiction book by Jessica Bruder, she takes this nation’s wide-open spaces and examines both their charm and their loneliness, stunning visuals embedded in a tale of economic hardship. Her characters, aging blue-collar workers, struggle in the fraught post-2008 financial landscape that makes retirement, not to mention home ownership, a distant fantasy. Nomads all, they wander the roads either in vans retrofitted to be simultaneous sleeping stations, or towing campers, sometimes part of migratory caravans of similar souls, sometimes on their own. Often bleak, occasionally heartwarming, and always poignant, Nomadland speaks not only to our time, but to the lost promise of the past.

OTHER FILMS (Also in Alphabetical Order):

Days (Tsai Ming-liang, 2020)

I was a big fan of his 2013 Stray Dogs (the only other film of his I’ve seen, so far), and Taiwanese filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang continues in much the same aesthetic vein with his newest work, Days, using long-duration takes and static compositions to offer meditations on the slow progression of time. It’s often stunningly beautiful, if austere, with a poignant story of (missed) connection at its center, but it didn’t quite resonate for me as did Stray Dogs. It is still well worth the watch, however.

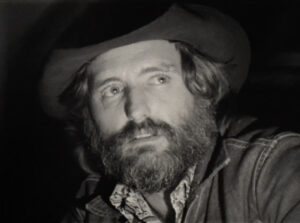

Hopper/Welles (Orson Welles, 2020)

Here is the description from the NYFF site: “This entertaining and revealing footage, never before seen in full, has been resurrected by producer Filip Jan Rymsza and editor Bob Murawski, who helped bring Welles’s unfinished The Other Side of the Wind to meticulously restored life two years ago.” And what is that footage? A 1970 conversation between Dennis Hopper, then hot off the success of his 1969 Easy Riderand in the middle of shooting The Last Movie, and Orson Welles (Citizen Kane), by then far past his prime. It’s really just as advertised, however – a filmed conversation between the two men – and not really a movie, though essential viewing for cinephiles. The camerawork, by Welles’s collaborator at the time Gary Graver, is all over the place, but there are definite gems amidst the blather.

The Human Voice (Pedro Almodóvar, 2020)

The first English-language film from celebrated Spanish auteur Pedro Almodóvar (Pain and Glory), based on French playwright/filmmaker/all-around-general-artist Jean Cocteau’s eponymous drama, The Human Voice (a 30-minute short) features actress Tilda Swinton (The Dead Don’t Die) in a simmering rage, jilted by her lover and looking for any opportunity to strike back. The story was the inspiration for Almodóvar’s brilliant 1988 Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown. Unfortunately, though the director’s usual fine production design is on display, made more evocative by the entire set built, obvious for all to see, inside a movie soundstage, something is lost in translation. It may entice the eye, but it leaves the mind and heart unmoved.

The Monopoly of Violence (David Dufresne, 2020)

An often intriguing look at the “Gilets jaunes” anti-government protest movement that began in France in late 2018 and still, in some form, has continued since, resulting in many injuries to demonstrators and little to no accountability for the police (sound familiar?), David Dufresne’s The Monopoly of Violence eschews traditional documentary techniques to plunge us into the middle of a series of conversations that address the issues of the moment. Supplemented by raw first-person footage from the streets, it offers profound debates on what law and order mean in a democracy, and who has the right to violence ostensibly undertaken in the name of both. Unfortunately, the film also lacks context, assuming that the viewer goes in already knowing the circumstances that led to the protests, and does not identify its many subjects until the end. It still fascinates, however.

The Salt of Tears (Philippe Garrel, 2020)

It turns out I am no great fan of the work of French director Philippe Garrel, at least based on my reaction to his 2017 Lover for a Day and The Salt of Tears, his latest (I have not seen any of his earlier films, nor now have any plans to do so). Though at least this movie directly addresses the toxic masculinity that he presented without much commentary last time around, his relentless focus on the naked bodies of much younger women detract from whatever larger issues he wishes to discuss. He gives French cinema a bad name. Hard pass.

Stay tuned for another roundup after the festival ends.