Film Review: “Bully. Coward. Victim. The Story of Roy Cohn” Tells the Story of Its Subject, Once Again

Written by: Christopher Llewellyn Reed | June 17th, 2020

Bully. Coward. Victim. The Story of Roy Cohn (Ivy Meeropol, 2019) 3 out of 4 stars.

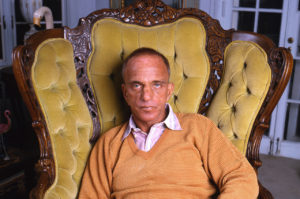

The late Roy Cohn is having quite a moment in the past few years, or at least his ghost is, starring in not one, but two documentaries and acting as a shadowy wraith behind the would-be imperial presidency of Donald J. Trump. That first film, Where’s My Roy Cohn?, from director Matt Tyrnauer (taking its title from a question attributed to the current occupant of the White House), came out in 2019, and was comprehensive in its historical approach, offering viewers all they need to know to understand the life and career trajectory of the man responsible for sending Ethel and Julius Rosenberg to the electric chair. Cohn’s crimes against humanity go far beyond that original sin, however, and include working for the mafia, teaching the young Trump how to never say you’re sorry, and promoting vile anti-gay policies while himself a deeply closeted homosexual. He died in 1986, at the age of 59 of an AIDS-related illness, and while one might be tempted to feel sympathy for the lie he was forced to live, even a cursory examination of his deeds absolves one of the need to so engage. He was a nasty piece of work, plain and simple.

Now comes Bully. Coward. Victim. The Story of Roy Cohn, from Ivy Meeropol (Indian Point), who just happens to be Ethel and Julius’s granddaughter. Though she treads many of the same narrative paths previously walked by Tyrnauer, Meeropol brings in, as one would hope, the additional angle of her own family history, interviewing her father, Michael Meeropol, at length and showcasing his 1970s crusades to rehabilitate his parents’ image and excoriate Cohn’s legacy. Her title comes from the surprising caption on a 1988 AIDS quilt that called out the aggressive, pathetic and tragic qualities of Cohn’s life. Born in 1927 in the Bronx borough of New York City, he was a gay, Jewish man at a time in American life when neither were seen as net positives, and grew up both pampered by his doting mother and terrified of exposure. His hunger for power led him down many a twisted rabbit hole, all presented here for us to ponder.

Filling her movie with similar interviews as did Tyrnauer, Meeropol also includes additional talking heads, beyond her father, including: Cohn’s former driver Peter Allen; New York Post gossip columnist Cindy Adams; playwright Tony Kushner, who wrote Cohn into his monumental Angels in America; journalist Peter Manso, who interviewed Cohn for Playboy magazine in the early 1980s; and filmmaker John Waters, who saw Cohn partying it up with drugs and young lovers in the gay mecca of Provincetown, Massachusetts. The result is an always watchable meditation on how depravity is enabled by those who tolerate wrongs out of convenience. Given that Meeropol spends significant time (more than Tyrnauer) on the Cohn-Trump relationship, her film is replete with unspoken parallels between the seemingly invincible aura of Roy and today’s cult of Donald. Perhaps the latter should heed the lessons of what happened to his mentor, especially since he was one of those who abandoned him when his star fell. Live and learn, or not.

This is hardly a good movie to watch after seeing Where’s My Roy Cohn?, however. I actually preferred that earlier work, though it may be because I saw it first. I’m just not convinced that Meeropol’s personal connection leads to a greater understanding of her subject. I also found the constant use of the word “evil” to describe Cohn as overly simplistic. Such designations let the rest of us off too easily, since it takes a village to make a monster. The perpetrator of the heinous act is most guilty, but those who fail to hold such people accountable are not much better. Still, if one has not yet seen Tyrnauer’s documentary, this one will more than suffice.