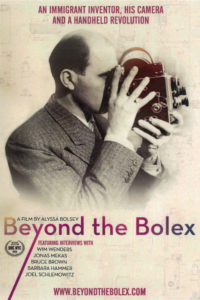

Interview with Director Alyssa Bolsey and Cinematographer Camilo Lara of BEYOND THE BOLEX

Written by: Christopher Llewellyn Reed | August 18th, 2019

I met with director Alyssa Bolsey and her cinematographer, Camilo Lara, at DOC NYC 2018 to discuss their collaboration on Beyond the Bolex (which I reviewed for Hammer to Nail). The documentary follows Bolsey as she investigates the life and work of her great-grandfather, Jacques Bolsey (born Bogopolsky, also known as Bolsky), who just happens to be the man who invented the Bolex camera. It is a profoundly personal movie, as the director explores the past and its influence on the present. Using archival footage from the vast treasure trove of materials she uncovers, Bolsey successfully evokes the era of cinematic invention in which her gloriously innovative ancestor did his best work. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Christopher Llewellyn Reed: So, let me start with you, Alyssa. You had early on manifested an interest in filmmaking, and yet until the death of your grandfather – Jacques’ son, Emil – you had no idea that your great-grandfather had invented the Bolex. How is it possible that no one in your family had said, “Oh, you like movies? By the way, did you know that your great-grandfather invented the Bolex?” That’s amazing!

Alyssa Bolsey: I wondered as well. It is pretty remarkable. I knew he was an inventor. But he also died 20 years before I was born. I think it was mostly just … no one in my family were filmmakers. They had no knowledge or interest. They knew he invented the Bolex, but that was just one of his early cameras, it wasn’t the camera he was working on when they were kids. So, it wasn’t until the perfect storm of me starting film school and the tragedy of my grandfather – his son – dying, that it came together for me, and I decided that I needed to look into it. And I didn’t know how big the Bolex was, right away. I had heard the word, I knew the name, but I had grown up with digital, so I didn’t really understand how big it was until I went back to film school and started talking to my professors about it, and slowly but surely I realized that this camera links generations of filmmakers around the world.

CLR: Sure. I’m a little older than you, so I played around with the Bolex in film school, as well as some other 16mm cameras. So, yes, as you discovered in the making of your film, it’s an incredibly important camera. What an amazing experience for you, to discover that in making the movie. So, how did you and your DP [Director of Photography], Camilo, meet to make this film?

AB: He’s also a producer on the project, and we were both working at CAA, the talent agency, in Century City. I had started the project years earlier and I put it aside for a couple of years, and it just kept calling to me. So, I quit my job there, telling people what I was doing, and they said, “Oh, you should talk to Camilo. He DPs on the side and he has a great eye.” So, we met for dinner and the rest is history. He’s been by my side for, what, seven, eight years?

Camilo Lara:Yeah.

AB: In the making?

CL: Seven, eight years now. We were acquaintances and knew each other at work, but we didn’t really work together, on different floors and everything. And I myself learned on a Bolex, so I have that story attached to me already, and that interest grew. And yeah, meeting Alyssa and having to see her passion and how much work she had already done to, you know, try and pull the story out, I was kind of inspired by her. I needed to jump in to make it happen, as much as I could.

CLR: Is there anything in this movie that was shot on film, on 16mm, anything like that? Or, is it all digital?

CL: Most definitely. The intention was for Alyssa to be using the Bolex as a catalyst for her to get to know her grandfather, so in the film she is using the Bolex. She shoots with it, and we show some of that footage, as well as all the archival stuff from her great-grandfather. We wanted it to stand out from the HD stuff. I know Alyssa can speak better to that aspect of it, because we did work on it together, but the brainchild of having to highlight this footage was Alyssa’s idea.

AB: What I really wanted this to be was a collision of eras. Me, being this digital-era filmmaker going into the past and meeting my great-grandfather and discovering the era that he not only lived in but helped develop the technology for. So, I wanted it to be the collision of the two, and as Camilo said, I felt that if we shot my journey on digital, when we did see the Bolex it would become more of a character because it would stand out more. Whereas if we had shot the whole movie on 16mm film, the Bolex wouldn’t …

CL: It wouldn’t shine as much.

AB: Yeah, it wouldn’t be highlighted as much.

CLR: I really liked the archival footage that you show of your great-grandfather’s films, the ones he directed and starred in, including the home movies. They’re really quite fascinating. I love that kind of visual family history that we have in the 20th century that we didn’t have before. So, obviously the film was always going to be personal to some degree, since it’s your great-grandfather, but you put yourself right in the center of the story, making it about your journey as much as about your great-grandfather. Did you ever think about a different structure or hesitate to put yourself in the story?

AB: Oh, completely. I planned on maybe being the narrator and you see me once, a couple times, and that’s what we were really shooting, which is why there isn’t as much vérité of me, because the journey was not shot in a vérité way. We didn’t have a second camera to capture me in most of the interviews.

CLR: Except there is one moment with your uncle where you’ve got two cameras running, which was very interesting.

AB: Yeah, that was later on when I decided to put my own story in, and we brought a second camera for some pickup shoots. And, I didn’t know … just to be clear, I did not know that was going to happen. I was going to tell him the story, I thought, about the dream I had with my great-grandfather. After working on this for 13 years, I only had one dream with him, and I thought I was just going to tell him this cool story and my uncle would go, “Wow, that’s interesting.” But it took a turn in another direction where I really realized for the first time how emotionally invested I was.

When I first started out, I felt very much like a detective, because I have so much distance from my great-grandfather. I had never met him: he died two decades before I was born, and my family had never really talked about him. I had the distance. I thought I could do this more like a journalist, but in the process of doing it, I started realizing that I was developing some kind of relationship and he was more like family. He literally is family, but I started feeling that bond. So, that’s when I started putting myself back into the film and we did some test screenings and people were like, “Wow, we really want to see more of your journey.”

CL: And that specific part was really interesting because all of a sudden you have this built-out camera. We had no space to place a second camera and were just like, “We just need to shoot this. Let’s forget about the rules.” And we just threw the camera that we were using for our still shots out there really quickly and recorded what we could, and it worked out. I mean, it was one of the most emotional moments we have in the film, that really digs deep into the whole core of where she’s at with it and why she’s doing what she’s doing.

CLR: Yes, I think if the emotional truth is there on the screen, it doesn’t really matter what the setup is or if you break the rules.

CL: Yeah.

CLR: So, speaking of how you were shooting things, there are a few, what I would call sort of mild recreations, right? With Alyssa handling the camera or opening books. How did you decide to stage those and go about doing that?

CL: Yeah. An early collective decision, for sure. Alyssa wanted to have two different looks, and we both said that was definitely the way to do it. From my side of it, it was, “Let’s create a very different palette, different tone, so that you get the sense that this is all being created, kind of like manifesting some of what was being done in his journal.” We weren’t sure how much of this is the truth or if he was just telling people stuff that he wants someone to eventually find and they’ll be reading this journal and that will be the story. Because he was fantastic at marketing himself, he was a genius at doing that.

So, we always had this … not trepidation, but a little bit of wanting to stay removed and be unbiased to what we were seeing, reading, and experiencing and allow that to kind of unfold. So that’s why you see warm tones when we’re upstairs in the attic, and then eventually it gets a little bit cooler, and so you’ll start to see more of a vérité look in the second half of the film. That was all intentional to try and bring that aspect of it more to the viewers’ attention.

AB: So, for the discovery scene, it’s definitely a recreation, and I didn’t want it to seem like it wasn’t. I wanted it to be what it was, but I also wanted it to be surreal, kind of like a memory, an idealized dream, almost, of what it was like. And then I wanted … as I got to know my grandfather better, and as the viewer is getting to know him, I wanted to pull away some of that artificial recreation and to really just dig deeper into what is the truth and what is real, and so, that’s when we started to, like Camilo said, make it more vérité. But in the beginning, I really wanted it to be almost like a painting of the memory.

CLR: You have a lot of really great talking heads, including with people like Wim Wenders and Barbara Hammer. How did you meet them and get them to be in your film? And were there any other people that you tried to reach out to who you didn’t end up getting in the movie?

AB: Each one was a different story, really. Sometimes I would interview one person and they would say, “Oh, you should really talk to this person.” A lot of people were really enthusiastic, and the ones that I have in the film were more than happy to do it. It didn’t require 20 phone calls to their agent; they were just really excited because they have a love for the camera, and it has figured in their life in a prominent way. And so, when they heard about the project, they were excited to be involved. It was more a matter of us finding the financing to go to where they were, and then finding a time where it worked. A lot of them were actually here in New York City, like Barbara Hammer, Jonas Mekas, Joel Schlemowitz, and even Wim Wenders was here when I filmed his interview at The Film-Makers’ Cooperative.

As far as people who we were trying to get into the film and it didn’t work out for various reasons, I really had hoped to have Peter Jackson do an interview, and we tried and they were interested but the timing didn’t quite work out. He figures in it, in the archival sense, but I wanted to maybe go a little deeper on that.

CLR: Same with Spielberg. We have this footage of his early films …

AB: Yeah.

CLR: … but he’s not in the movie.

AB: I was hoping to make that work out and I wasn’t able to, but he did allow me to use that footage, which was very nice.And, let’s see, who else?

CL: I mean, there were a lot of people. We definitely were also trying to get Spike Lee, but sometimes things just didn’t work with the schedules. That’s usually what ended up happening. Also Michel Gondry, Christopher Nolan, or … sorry, not Nolan, but Fincher. Did we?

AB: I don’t think so.

CL: That’s right. Sorry. We just needed to get the rights to show a part of his movie. We weren’t trying to get an interview.

CLR: Understood. So, it makes sense that these are all people who are all partisans of film …

CL: Yes.

CLR: … who would in some way be interested in being part of the movie. What did you shoot the interviews on, since you didn’t shoot them on film?

CL: Since this project was so long, we kind of evolved with the technology. The initial stuff, that was development material, which we ended up using some of, was shot on Canon cameras, usually. We started with a 7D and a 5D, but most of that stuff didn’t make it into the film. We then upgraded and were using a C300. Most of the things that we shot for the recreated scenes, or that have that one tonal look, that’s the camera that we use for that, and the cameras that we used prior … we intended to work that footage together so we would match that look. All the vérité stuff was shot on Sony cameras. The majority of the time it was an FD5 or an F5, and we had pickup shoots here and there. We didn’t have quite the budget to bring those cameras back, so we opted to use a Sony a7S Mark I and II, as they came out, and we had planned ahead of time, setting log values that we were going to be able to match.

And we did a lot of learning, growing up, you know, on this film, so by the time we had got to the portion where it really mattered, the majority of the film was going to be shot on the Sony cameras, and we were really able to dial that in and already be aware of how to make this match. So, I feel like in the film it’s pretty seamless, in some ways. I mean, there is stuff that pops out, but it’s meant to; that’s the Canon stuff that you’ll end up seeing that tends to kind of look really well-crafted, well-lit, and that’s what we did, specifically for that look, with those cameras.

AB: And we should also mention that we worked with another cinematographer, as well, Joseph Areddy, for the Switzerland footage.

CL: And some other … we got some other really great shooters that were with us. Like Pietro …

AB: Yeah, and usually when it was one of them shooting, Camilo would wear more of the producer hat, or the gaffer hat, because he has a great eye for light.

CLR: So, how long, then, from start to finish, did it take to make this movie? You talked about the changing technology, so this was a really a long process. Your grandfather died in 2004, right?

AB: Yes.So about 13 years.I took a year or so off in between, but, yeah, 13 years basically. When I first started, I had a Panasonic DVX100A.

CLR: I know that camera well!

AB: And, yeah, technology completely changed between then and now.

CLR: Did you ever approach the makers of the Digital Bolex to include that camera in the movie?

AB: Yeah, I did. We followed their journey, and there’s a European TV cut for ARTE where we have a little bit of their journey in our 52-minute version. But, for the feature version, I wanted it to be focused on Jacques and his struggle and the journey to uncover him and the users. But, I definitely respect them a lot for what they did, and I think that was really incredible to invent a camera, basically, or create a version of a camera in this day and age when there are all these huge, giant corporations … to even try to compete, I super-respect that.

CLR: Well, congratulations on the film. I really enjoyed it.

AB: Thank you so much!

CL: Thank you so much, we really appreciate your time.